The man who literally wrote the laws on presidential transitions is now running one — and it could be the country’s most difficult handover of power since the Great Depression, with dueling health and economic crises as well as an unpredictable incumbent who may throw wrenches into the process.

Ted Kaufman, Biden’s longtime chief of staff in the Senate and head of his 2020 transition effort, likely has more control over a future Biden administration than anyone other than the Democratic presidential nominee himself. That makes him one of the most popular men in Washington now, as job seekers angle for potential posts and lobbyists try to divine his intentions.

Kaufman has his fans on the left, thanks to his tough stance on the banks during a short stint as a senator after the 2008 financial crisis. He has friends in the center, who say he and Biden share the same strand of moderate politics. Kaufman’s animating force, however, is an almost quaint belief in the American government’s institutions, friends and allies say.https://faea1363208c2c25a2d5aaad4fed2813.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-37/html/container.html

As head of Biden’s transition team, his ambitions go beyond just an efficient hand-off of power and extend to proving that the federal government can actually work — andthat bipartisanship isn’t extinct.

A bomb thrower he is not, and he is unlikely to hire many, either. Given the myriad crises facing the country, Kaufman is likely to favor competence and experience over ideology, allies say. That could disappoint some of Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Sen. Bernie Sanders’ left-wing allies, who are hoping to join the administration but might lack the governing experienceof those who worked under former President Barack Obama. His disposition could similarly freeze out swampy strivers looking for a resume line.

“He is going to be looking to avoid people who give off the impression that they are first looking out for themselves — people who want to work for the administration for a year or two and then go monetize their service,” said Alexander Mackler, Kaufman’s deputy chief of staff in the Senate and now Delaware’s chief deputy attorney general. “He has been clear for a long time that he doesn’t look kindly upon the revolving door.”

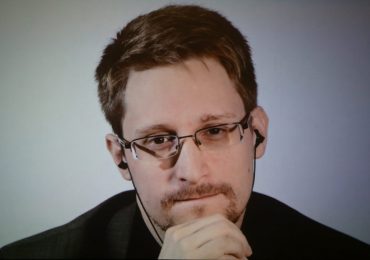

Kaufman, a wiry 81-year-old with a receding but still unruly head of hair who one former aide compared (admiringly) to Rafiki in The Lion King,was appointed to Delaware’s Senate seat in 2009, filling the vacancy created by his boss’ election as vice president. He was a placeholder, serving only until a special election was held in November 2010. But he carved out a legacy that continues to reverberate today, at least inside the Beltway, in the wonky world of the federal bureaucracy.

Kaufman regularly gave speeches on the Senate floor singling out obscure bureaucrats for a job well done as part of a larger “Great Federal Employees” initiative. In his farewell address, he warned against altering the Senate’s filibuster rules as the left wing agitated for changes — calls that have only gotten louder since. ”The existence of the filibuster remains important to ensuring the balanced government the Framers envisioned,” he said at the time. Asked if he still supported keeping the filibuster, Kaufman did not respond.

At an event hosted by the Wall Street Journal over the summer, Kaufmanargued that the country’s polarization is not a permanent state. “The problem we have is a lot of people that are covering this [moment in politics] haven’t been covering the country for long. They think it’s always been like this,” he said. “It hasn’t always been like this. This is a relatively recent thing, like, really in the last 10 years. I mean, back before that we really did get along.”

Some on the left and the right appreciate the sentiment but believe it’s naive or too nostalgic for a past that is now out of reach.

“In 2010, [Senate Majority Leader Harry] Reid was still defending the filibuster … and a lot of people’s views have changed since then including Reid’s,” said Adam Jentleson, Reid’s former deputy chief of staff and the author of an upcoming book on the modern Senate. “The formative experience of people like Kaufman was an anomalous period. That was a different time and it’s not coming back.”

Kaufman drew similar eye rolls when he suggested this summer that Democrats would not be able to spend money on a lot of new initiatives because the “pantry is going to be bare” after the Trump administration’s spending. He even seemed to be at odds with Biden’s longtime economist Jared Bernstein who said this month that “we must fight tooth and nail against the return of austerity politics.”

Kaufman’s belief in functional, bipartisan governance is at the core of his work on presidential transitions, which requires cooperation across agencies and parties. Indeed, Kaufman’s leadership of Biden’s 2020 transition team is the culmination of more than 10 years aimed at forcing presidential candidates to take transition planning more seriously: requiring they start preparations for a transfer of power earlier and providing more financing for staff and other needs.

“Campaigns grew concerned about the negative impact it could have on their winning, to be seen as preparing publicly,” said Max Stier, the president of the Partnership for Public Service, a nonprofit focused on the civil service. ”It makes, from a public policy sense, not a lot of sense. But it was a political reality.”

In 2010, Kaufman’s bill, the “Pre-Election Presidential Transition Act,” was enacted to law, authorizing more government resources to transition teams before the election. After leaving the Senate, Kaufman teamed up with Stier andthe head of Mitt Romney’s 2012 transition team, former Utah Governor Mike Leavitt, to help pass another law in 2016 that further formalized the transition procedures.

Congress even named the law after them — the ”Edward ‘Ted’ Kaufman and Michael Leavitt Presidential Transitions Improvements Act.”

“He was most passionate about the needs for candidates to understand that it’s not an option, it’s an obligation,” Leavitt recalls. “That was the fundamental shift, that candidates know it was an obligation.”

Biden, an old-schoolpol, was one of those candidates who has needed convincing. As the vice presidential candidate in 2008, the then-Delaware senatorhad been wary of jinxing the election by focusing on what would come after victory, Democrats around him at the time recall.

“Before the election, Biden was more superstitious about not wanting to get too much information,” recalls John Podesta, who was leading Barack Obama’s transition effort at the time. “He just wanted to be out campaigning.”

So Biden delegated the vice presidential transition work to Kaufman and longtime aide Mark Gitenstein, who is now on the transition’s advisory board. For Kaufman, it was a life-changing experience that would lead him to become something of an obsessive in the obscure world of presidential transition work.

“At the time, we were in the financial crisis and so I think he had a real appreciation for the fact that a successful transition was critical to successful governing,” Podesta said.

Kaufman seems to have gotten through to Biden since then, at least a little — the Democratic nominee has appeared less skittish this go-around, and regularly gets briefings from the team.

“If you could clone Joe Biden for this job, you would create Ted Kaufman,” said Gitenstein. “They are very similar with their values and upbringing.”

So it was almost a given that Biden would tap Kaufman to lead preparations for his potential administration. He started early, calling people as recently as March to get started. On top of the many public crises, he’s also having to organize most of it via Zoom, although transition officials are impressed by the octogenarian’s tech savvy.

Yohannes Abraham, who runs the transition’s day-to-day operations, said that, “He can sit on a group Zoom call and tell, with extraordinary accuracy, when someone is upset, or doesn’t agree, or has something on their mind.”

Leave a comment